- News

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law Firms

- Apprentice Lawyer

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

The term "elokeshi" means "woman with dishevelled hair" – a description for the ferocious Goddess of Destruction, Kali. The protagonist of our story was also feared. Not for her strength to fight demons, but precisely on account of the demons that infected the minds of the people of that time - the fear of an independent woman with a mind of her own!

As a little girl in British-ruled Bengal, her life followed the usual pattern – an early marriage to free the father of the burden of having an unmarried daughter, and then a long wait to grow up and be sought out by the husband. Till then, Elokeshi was condemned to live in her village Kurmul in the “safe” keep of her father Nilkamal Mukhopadhyay and step-mother.

Elokeshi had been wedded to a high caste Kulin Brahman, Nobin Chandra – the dream come true for any Bengalee father in those times. In fact, in the high tide of polygamy, many Kulin Brahmans made marrying young brides their occupation. They would criss-cross the Bengal countryside, going from village to village, obliging desperate fathers by marrying their daughters. It is rumored that when some Kulins passed away, their pyres burnt for days as there would be a formidable line of brides in queue to commit Sati!

Mercifully Nobin was not that kind. He loved his Elokeshi.

Kurmul was only 70 kilometers away from Calcutta, the Queen Bee’s chamber in the honey comb of the Empire, which attracted people from far and wide. Nobin Chandra, who had recently secured a government job at the printing press, was no exception.

Yet, he thought it wise to leave his young bride in her father’s care. Calcutta was no place for an uneducated village girl. She would be safer and better off away from the evils of the city, the young man thought. After all, whenever he could take leave, he would make it a point to go and visit his child bride.

Life was blessed. Nobin’s only regret was that he desperately wanted a son, an heir. Elokeshi assured her husband that this was her wish too and that she had not spared any efforts. In fact, she had, in 1872, even reached out to a holy man to seek divine interdiction. The Holy Mahant, or priest of Taraknath Temple, Madhavchandra Giri had taken her under his protection and assured her that she would be blessed with a child soon.

On May 24, 1873, Nobin Chandra visited Elokeshi. On May 27, he used a boti or a fish knife to slit his sixteen year old wife’s throat. Full of remorse he surrendered before the local police sobbing “Hang me quick! This world is a wilderness to me. I am impatient to join my wife in the next”. He was promptly produced before the Joint Magistrate of Sreerampur, who ordered him to hajat.

Crime Statistics of Bengal for 1870-1875 reveal that 20-40 percent of murders every year were of “women involved in intrigues”, a euphemism for women suspected of being involved in extra-marital affairs. Why this case captured the society’s imagination in the manner it did was that it involved the high-profile priest.

This is the story of the two scandalous trials that followed, which rocked the very foundations of the colonial government and a colonized people, and charted how the colonial judicial system would administer English justice to natives who were so taken by the novelty of the English legal system!

The Hoogly Sessions Court at Serampore took up the case of Queen v Nobin Chandra Bannerjee. The local papers reported it as the “Tarakeshwar Murder Case”!

At his trial, Nobin Chandra’s defence was grave and sudden provocation. His defender was none other than Woomesh Chandra Bonnerjee, of Indian National Congress fame. Bonnerjee reportedly defended Nobin pro bono. Bonerjee argued that his client just could not control his rage when he found out that his Elokeshi had become intimate with the Mahant. He also claimed that when he had confronted his wife, she had confessed to the affair and the couple decided to shift her from her parents’ house as the Mahant had a hold over them.

However, when the father leaked the plans to the Mahant, his goons prevented the escape. Nobin was determined his Elokeshi would not be any one else’s, and hence, the decapitation followed! Bonnerjee, of course, before submitting this explanation, as would a lawyer of his skill would, exposed the hollowness of the prosecution’s case – there was no body of Elokeshi examined medically. Was she really dead?

Anshika Jain writes,

“The case had all the ingredients of a pot boiler - an affair, a murder and a killer who was also cast in the role of a victim.Naturally, it fired public imagination.As always with a case this complex, there were multiple narratives.One was about Nobin’s right to ‘uphold’ his honour; the second was the shock at how a Mahant could have taken advantage of a teenage girl; and finally, there was the issue of the British justice system, which was seen as interference in local matters.In a nutshell, the affair triggered a clash between a native sense of justice and the larger injustice as viewed by colonial laws.”

The Bengalee remarked, “People flock to the Sessions Court as they would flock to the Lewis Theatre to watch Othello being performed.” The press played no small a part. The case was relentlessly covered and “papers were highly selective in terms of what they reported and liberally sprinkled the news with editorial comments”.

The Court proceedings were disturbed several times. The Mahant and his English lawyer had also been attacked outside the court. Things got to such a stage that authorities had to charge an entrance fee and also insist that visitors be conversant in English as the British lawyers and the judges also spoke in the Queen’s language!

The Indian jury bought the defence and acquitted Nobin on the plea of insanity. The British Judge Charles Dickenson Field would have none of it. From January 1, 1873, the law had been modified to permit the British judges to disagree with the “native sense of justice” which had led to several acquittals. The judge could refer such a case to the High Court.

The Sessions Judge did just that. He overruled the jury verdict and forwarded the case to the Calcutta High Court. Field did, however, accept that there was an “adulterous relationship between Elokeshi and the Mahant as she was seen “joking and flirting”!

The courtroom and civil society broke out in protest at the reversal of the decision of the Indian jury. Swati Chattopadhyay writes:

“The Court proceedings were seen as an interference by the British in local matters. The court represented a conflict between village and city, the priest and bhadralok (Bengali gentleman class) and the colonial state and nationalist subjects.”

The trial of the Mahant for adultery (which was a criminal offence in India but had only a civil consequence in Britain) also had an interesting trajectory. Since adultery was a crime against the individual, Nobin had to bring the charge under the newly minted Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code that Thomas Babington Macaulay had authored just a decade ago. The Mahant had escaped to the French-ruled Chandannagore, where adultery was not a criminal offence. Joykrishna, an influential zamindar of the area, helped the British government to secure the Mahant.

He was tried first by the Hooghly judge and two assessors - Shibchandra Mallik and Shambhuchandra Gargory. The Mahant was defended by Mr Jackson and GH Evans, two well-known British lawyers of the Calcutta Bar. The government was represented by Ishwarchandra Mitra, a government pleader. The three points were:

(a) whether Elokeshi was the lawfully wedded wife of Nobin Chandra;

(b) whether there had been intercourse between the Mahant and the wife; and,

(c) whether the Mahant had knowledge of her marital status. Gopinath Sinharoy, the Mahant’s durwan (gate keeper) turned out to be the key witness and his depositions were religiously reported in the next day’s papers, to an enthralled public!

As the assessors were split, with Gargory holding that there was no direct evidence of sexual intercourse, the Sessions Judge convicted the priest and imposed a punishment of three years’ rigorous imprisonment and a fine of Rupees 2,000. The Mahant rushed to the High Court against this verdict.

Justices Markby and Birch, who decided the case in the High Court on December 15, 1873, also accepted the evidence proving adultery. Both husband and lover stood convicted. Controversially, when justifying the criminal conviction for adultery, the Court strained to express sympathy with the Hindu sentiment, and asserted and recognized the husband’s complete authority over his wife’s body. On the Mahant’s conduct, Justice Birch was merciless. Observing:

“(if he) is faithless to his trust, and if under the cloak of religion, and regardless of the decided prohibition of such conduct in the writings which he holds sacred, he employs his opportunities to debauch married women, he merits condign punishment."

Geraldine Forbes writes,

“In fact, the British saw Indians as demanding justice when attacked by thieves, but ready to defend men who murdered their unfaithful wives. While the British Judges sympathised with Nobin, they placed the law above personal revenge and individual justice.”

Nobin got transportation for life to the Andaman Islands. Within a year, the Mahant was transferred from Hooghly to the Presidency Jail and Nobin was on his way across the Bay of Bengal, to Andaman!

The frenzy did not cease. The local papers, which had carried a day-to-day coverage of the case, continued to bestow attention to the scandal for months thereafter, as the case had captured the imagination of the Bengalee society like none other. Elokeshi merchandise such as Saris, fish knives, and betel-leaf boxes flooded the market. They were on sale till as late as 1894. One headache balm company even advertised that in the making of its product, it used the oil made by the adulterous Mahant in the jail oil press.

A 10,000 signature mercy petition was moved by “acknowledged leaders of native society” demanding that Nobin be pardoned. They also felt that the Mahant had gotten away too lightly!

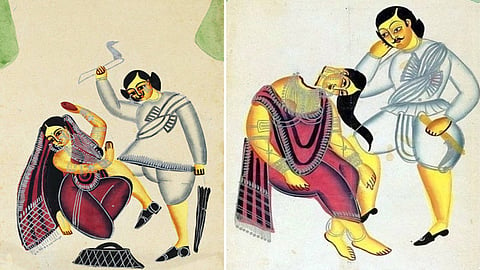

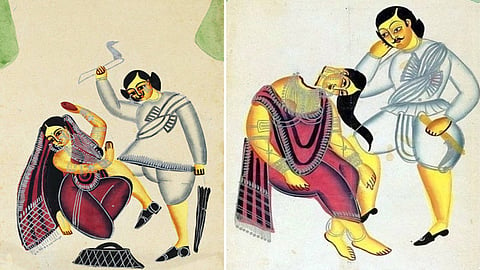

The pata-chitra artists of Kalighat have painted the gruesome killing of that sixteen year old as well as “amourous” scenes of her offering betel-leaf to a seated Mahant. Such paintings were in great demand as society could not have enough of a woman touched by scandal. It was not important whether actually there was any truth to the allegations.

Sanjay Ghose is a Delhi-based advocate

Watch our interview with Sanjoy Ghose