- News

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law Firms

- Apprentice Lawyer

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

Michelle Chawla & Kerban Anklesaria

1996 was a turning point in the history of Dahanu, a small region in the northwest of Maharashtra.

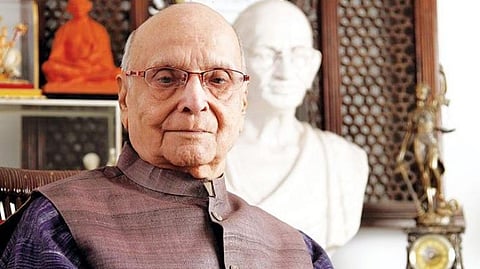

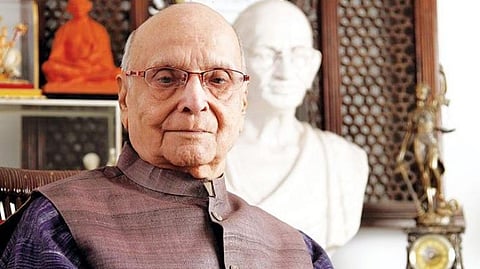

It was the year Justice Chandrashekar Shankar Dharmadhikari was appointed to head a special Authority to protect Dahanu’s lands, forests, coasts and farms from unchecked industrialisation, and to make sure there was planned development for its communities.

For the environmentalists, this order from the Supreme Court was a landmark one, since it gave a nondescript region like Dahanu, a “special” stature, that even other highly ecologically fragile areas in the country did not have.

At a time when most such Committees in the country were paper tigers, this was not to be.

Justice CS Dharmadhikari was the son of Damayanti Dharmadhikari and Acharya Dada Dharmadhikari, freedom fighters, Gandhians and leaders of many social reform movements. His Wikipedia page talks about his life as a lawyer, judge and highlights his landmark judgment during the Emergency.

The communities of Dahanu hold him dear for attempting to change the narratives of environmentalism by opening up a new space for engagement, dialogue and debate across power structures.

Practicing anthropocentric environmentalism, coupled with his Gandhian and socialist values, Justice Dharmadhikari directed a Supreme Court appointed Authority on core values of social justice and equity.

When Tukaram Machi, a fisherman from Pale village in Dahanu, complained that the water released from the local power plant was too hot, affecting the marine life and making it difficult for estuarine fisherman to lay their nets, the Authority ordered an immediate site inspection and testing of the outlet of water at the plant site in the presence of community and civil society representatives.

Since its first meeting on May 6, 1997, the Authority has held over 45 meetings over a span of 20 years, addressing diverse environmental and developmental issues such as the construction of a mega port, pollution control of a thermal power plant, sea water ingress on coastal communities, building of national highways, laying of high-transmission towers, and preparation of a Regional and Development Plan for the Taluka.

Functioning almost like a people’s court, the Dahanu Authority, supported by 11 expert members, invited to its meetings members of concerned government departments, elected representatives, community and civil society groups, corporations and agencies interested in undertaking work or projects in Dahanu.

While there was a formal tone to the meetings, the charisma in which Justice Dharmadhikari conducted them made them both provocative and enthralling.

He had a way of addressing everyone – activists, officers, bureaucrats – that made them feel humbled before a very inspiring teacher. Even industrialists, politicians and businessmen with contrary values and opposing views could not completely ignore many of the complex nuances of development as pointed out by him.

During the period of 1997 to 1999, the Dahanu Authority held a series of meetings to decide if a mega port at a small coastal village in Vadhavan, Dahanu could be allowed in the declared ecologically fragile region. This involved submissions and deliberations from all parties: the Australian company that proposed the port, the Maharashtra Maritime Board that was supporting it, along with the affected communities, environmentalists and lawyers.

In a time when India was liberalising and in the frenzy of development, Justice Dharmadhikari was able to stand against the tide and pass an order declaring that the port could not be allowed in the coastal town. This was an order of conviction and courage.

Justice Dharmadhikari’s uprightness instilled both respect and fear.

Bureaucrats accustomed to working within the system, were suddenly faced with a new reality and an almost alien set of values — of truth and accountability. Corporates and even public sector companies saw the Dahanu Authority as a major road block to their projects, being forced to answer questions and “buy the peace”, as the Chairman often reminded them of the structural inequities in our society.

Bringing to task a corporate giant like Reliance took several years and a mammoth amount of work by the expert members of the Authority and civil society groups, who had to scientifically establish the need for a pollution control system like the Flue Gas Desulphursation (FGD) plant for the thermal power plant in Dahanu.

The company not only refused to comply with the various directions of the Authority, but also challenged in the Bombay High Court Justice Dharmadhikari’s landmark order of committing to install the FGD Plant with a bank guarantee of Rs 300 crore.

In a David versus Goliath story, the appeal was rejected by the High Court, and the company had to provide a bank guarantee of Rs 100 crore till they could establish the FGD Plant in Dahanu in 2005.

Needless to say, it was Justice Dharmadhikari’s strong beliefs in deliberation and due process that gave strength to the efforts of the members of the Dahanu Authority as well as lawyers and scientists who sustained a prolonged and confrontational campaign against a potential environmental threat.

The communities of Dahanu are largely sheltered from the indiscriminate pollution that comes along with a coal fired plant largely because of the rigourous manner in which a continuous check was kept on the power plant with frequent inspections, submissions of pollution data, and a bold Authority.

His insight, legal acumen, and above all, his skill to give priority to human rights while rendering environmental justice is unmatched in the annals of environmental law in India. His experiments with environmental justice were purposeful and examined so that even though some of his orders were pathbreaking during the formative years of environment law in India, his decisions were accepted by all concerned parties.

Two examples of his many path-breaking decisions are the implementation of the “precautionary principle” and his concept of pre-afforestation to ensure that loss of forest cover is compensated prior to actual loss while implementing infrastructure projects.

Several thousand trees stand tall across the afforestation projects in Dahanu as a testimony to his work to develop Dahanu sustainably.

In over 20 years of his heading the Dahanu Taluka Environment Protection Authority, and dealing with a minimum of 100 environmental issues, only one decision of his has been appealed against in a higher court (against the FGD Plant).

This is an achievement that probably no authority in the world can speak of and is the ultimate test of a judge’s sense to do justice.

These achievements of the Dahanu Authority were a direct result of the moral fibre of Justice Mr CS Dharmadhikari and his ability to harness law, science, expert opinion, good will, and cajole parties to seeing reason and most importantly find the most appropriate solution to complicated questions of competition for natural resources in an ecologically fragile region.

Justice Dharmadhikari passed away on January 3, 2019, at the age of 91.

This article was first published by The Medium.

Image Courtesy: India Today