- News

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law Firms

- Apprentice Lawyer

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

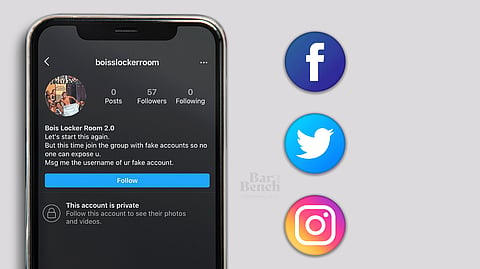

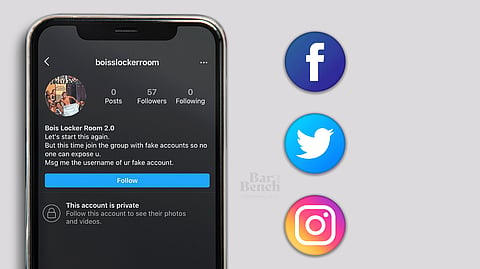

The “Bois Locker Room” incident recently caused a wave of outrage across the entire nation.

The incident came to light when multiple screenshots of Instagram group chats were leaked, thereby exposing the group where images of girls, including minors, were shared, and girls were objectified and shamed using offensive and vulgar language. There were also alleged comments and discussions to commit heinous and gory crimes against their modesty, including threats of sexual violence.

The participants were school-going teenage boys who created the group to share pictures of girls, most of whom were below 18 years of age.

As much as the incident brought out the need for gender education in every household, it also raised questions regarding the role of intermediaries that provide platforms to users to host such criminalistic conversations.

An intermediary is defined under Section 2(w) of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) as under―

“2. (w) “intermediary”, with respect to any particular electronic records, means any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits that record or provides any service with respect to that record and includes telecom service providers, network service providers, internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online-auction sites, online-market places and cyber cafes.”

Intermediaries enjoy protection from liability under Section 79 of the IT Act, in certain cases:

(i) when the function of the intermediary is limited to providing access to a communication system over which, information made available by third parties is transmitted or temporarily stored or hosted; or

(ii) when the intermediary does not initiate the transmission, select the receiver of the transmission, and select or modify the information contained in the transmission; and

(iii) the intermediary observes due diligence while discharging his duties under the IT Act and also observes such other guidelines as prescribed by the Central Government in this behalf.

However, this is not a blanket protection granted to intermediaries in view of Section 79(3) of the IT Act, which stipulates that an intermediary shall not be exempt from liability if:

(i) the intermediary itself has conspired or abetted or aided or induced, in the commission of the said unlawful act; or

(ii) if the intermediary, upon receiving actual knowledge, or on being notified by the appropriate Government that any information, data or communication link residing in or connected to a computer resource controlled by the intermediary, is being used to commit the unlawful act, and the intermediary fails to expeditiously remove or disable access to that material on that resource without vitiating the evidence in any manner.

Section 79 of the IT Act was upheld by a Division Bench of Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, “subject to Section 79(3)(b) being read down to mean that an intermediary upon receiving actual knowledge from a court order or on being notified by the appropriate government or its agency that unlawful acts relatable to Article 19(2) are going to be committed then fails to expeditiously remove or disable access to such material.”

Additionally, there is a duty cast upon such intermediaries under Section 20 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act to provide the necessary details and to report the commission of any such offence, within their knowledge, which is sexually exploitative of a child, to the Special Juvenile Police Unit, or the local police. Failure to report the commission of such offences shall be punishable under Section 21 of the POCSO Act for a term which may extend to six months or fine or both.

In 2015, the Supreme Court of India took suo motu cognizance of a letter addressed to it by an NGO named Prajwala, raising concerns about rampant circulation of videos depicting sexual violence like rape/gang rape/child pornography on online platforms like Whatsapp, Google, Facebook etc.

Thus, the Supreme Court impleaded Google, Facebook, WhatsApp, Yahoo and Microsoft as parties and directed that a committee be constituted to advise the Court on the feasibility of ensuring that videos depicting rape, gang rape and child pornography are not available for circulation.

The matter is still pending its final outcome. Yet, there was a consensus within the committee that the websites and portals that do not proactively censor content that depicts sexual violence should be blocked by law enforcement agencies.

Pursuant to this, the government launched a cyber-crime portal for reporting such incidents and recommended a photo DNA software for blocking such content at the threshold. It also set up proactive monitoring tools for auto deletion of unlawful content by deploying Artificial Intelligence-based tools. The Court also suggested the creation of a government-controlled hash bank of such content.

However, with a view to increasing the role of intermediaries in actively monitoring the content so circulated, on March 9 this year, the Government of India notified the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Rules, 2020 (POCSO Rules).

Rule 11 of the POCSO Rules makes it categorically clear that an intermediary, in addition to reporting the said offence, shall also hand over the necessary material including the source from which such material may have originated to the Special Juvenile Police Unit or the local police, or the cyber-crime portal (cybercrime.gov.in).

The report shall include the details of the device in which such pornographic content was noticed and the suspected device from which such content was received, including the platform on which the content was displayed.

The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines) Rules, 2011 also casts an obligation of carrying out due diligence on the intermediaries, while discharging their duties, to publish the rules and regulations, privacy policy and user agreement for access or usage of the intermediary's computer resource by any person. These shall inform the users of the computer resource to not host, display, upload, modify, publish, transmit, update or share any information which is so prohibited. The said Intermediary Guidelines were upheld by the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal, subject to the same limitations put on Section 79(3)(b) of the IT Act.

Singapore was recently faced with a similar challenge with respect to the circulation of fake news through such social media platforms. Therefore, Singapore enacted the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, 2019 (POFMA), which seeks to prevent the electronic communication of falsehoods and also provides safeguards against the use of online platforms for the communication of such falsehoods.

POFMA provides for various measures to counteract the effects of such communication and to prevent the misuse of online accounts and automated bots. Section 3 provides that POFMA shall squarely apply to all statements communicated to one or more end-users in Singapore, through the internet, as well as MMS and SMS. It makes it abundantly clear that POFMA will also cover social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter and other closed platforms, such as private chat groups and social media groups.

Part 4 of the POFMA specifically requires that an internet intermediary, whose service is the means by which a falsehood is communicated in Singapore, will be required to communicate a correction notice to all end-users who accessed such statement via that service.

Internet intermediaries may also be ordered to disable access to a declared online location, where the internet intermediary has control over access by end-users in any place to the declared online location. The failure to do so shall render the internet service provider or internet intermediary liable to a fine of up to S$20,000 for each day that the order is not complied with, up to a total of S$500,000.

Additionally, any Minister may issue an Account Restriction Direction to order an internet intermediary to shut down any fake accounts and bots on its platforms under the provisions of Part 6 of the POFMA. It shall be the duty of the intermediary to prevent the fake accounts from using its services to communicate falsehoods, and/or prevent the fake account owners from interacting with the end-users of its service in Singapore.

It is not enough for intermediaries in India to wash their hands clean, claiming no liability under the safe harbour clause, for offences being committed right under their noses, particularly when the sexual crimes on the internet are on the rise, in respect of both minors and adults.

Therefore, there is a crucial need for updated Intermediary Guidelines that shall highlight and remedy the abuse of social media platforms.

After various debates in the Parliament in 2018, regarding incidents of violence due to misuse of social media platforms, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology has prepared a draft of the Information Technology [Intermediary Guidelines (Amendment)] Rules, 2018. These guidelines amend the due diligence requirements for such intermediaries, and require them to deploy automated tools to identify and remove the unlawful content from public access.

However, the same have not yet been notified. Regardless, the same shall be rendered toothless if role of such intermediaries, in curbing the virtual offences as aforementioned, is not streamlined like that in Singapore. One can only hope that such incidents as “Bois Locker Room” and other cases of digital mob-lynching shall come to a halt once appropriate and more stringent laws are in place.

The author is an advocate practising before the Delhi High Court.